Where we are and how we got here

The mainstay of the UK’s residential property sector is the house, produced in its thousands by mass market housebuilders and still the ultimate dream of so many aspiring homeowners.

While houses have traditionally been designed for and associated with the nuclear family of mother, father and children, today’s households are far more diverse. The nuclear family is likely to be living next door to an extended or blended family, or alongside boomers, millennials, gen X or gen Z.

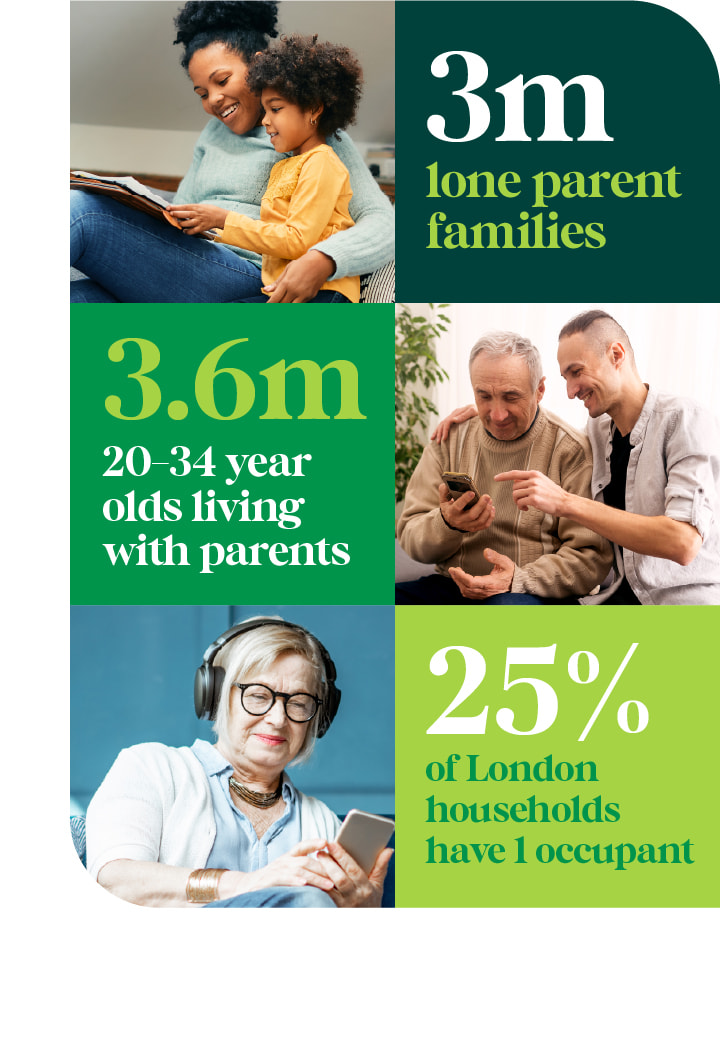

The UK’s 28 million households include 3 million lone parent families and more than 3.6 million people aged from 20 to 34 living with their parents, according to the Office for National Statistics. The number of people living alone has also risen dramatically, with the proportion of one-person households reaching more than 25% in London and 36% in Scotland. While owner occupation remains the dominant tenure in the UK, high property prices and a shortage of social housing have created huge demand for private rental homes, where prices have been rising by record levels.

These factors – alongside changing home aspirations and evolving working and living patterns, accelerated by the pandemic – are all having an impact on how people live and on the housing typologies and tenures now being provided in the UK residential market.

How we live now

Pandemic changes in employee working patterns and the rise of micro-enterprises are playing into choice of home location and use, with hybrid and home-based working removing conventional separations between home and workplace. Property company Vita Group has charted people’s changing attitudes, needs and aspirations of home in its Future Living Report 2022.

Its survey of hybrid workers found 10% of respondents had already moved home to accommodate working lifestyles and 19% more were considering it. Research looking at the aspirations of more than 1,000 business owners found 78% of respondents would move to a property if it had easy access to services and amenities to support the growth of their business or hobby income, with younger age groups being keenest to make the move.

The pandemic has increased demand for homes with other features, notably those associated with health and wellbeing. For example, property consultant Strutt & Parker’s report, Life moves: 10 years on, which is based on its latest Housing Futures Survey and a decade of research, found more than half of survey respondents were looking for a home with outside space as they thought it would benefit their mental health.

Going solo

While home ownership remains a popular aspiration, Strutt & Parker’s research found a third of 18-29 year olds would prefer renting over other tenures, for its convenience, flexibility and lack of responsibility for repairs and maintenance. These factors, and a consistency in quality and pricing often lacking in the private landlord sector, have made build-to-rent homes attractive to renters. Build to rent is rapidly gaining a foothold in the UK, with property body the British Property Federation (BPF) recording 78,000 build-to-rent homes completed and 185,000 more under construction or in planning.

A business model that was initially targeted at young professionals in the biggest cities, is now being extended to more locations and property types, including later living and family homes. “The diversification of product to single family residential and into secondary cities highlights how the sector has evolved to date and will continue to do so to cater to need,” BPF Director of Policy Ian Fletcher has said.

One variation of build-to-rent that largely remains the preserve of students and young professionals is co-living, which combines studio-style personal space with the community amenities you’d associate with an upmarket hotel. The Collective, in Canary Wharf, east London, is an example of the genre, having more than 700 serviced studios alongside a long list of communal spaces that includes a golf simulator, swimming pool, bar, cinema and co-working and meeting spaces.

Extended and blended family living

For younger professionals – as well as ageing grandparents – living in a multi-generational household is another option. More than a decade ago Manisha Patel, senior partner at architect PRP, drew on her own childhood experience to create a fresh model for multi-generational living. The result was a new housing typology combining a three-storey townhouse and a connected but separate two-store annexe, which was developed at Chobham Manor in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in east London. “I knew that housing design needed to reflect social change,” Patel says. “It wasn’t a typology known in the UK at the time, but forms of multi-generational living were already happening illegally – there was clearly a need.”

That need remains, with more than half of respondents in a survey of 1,000 UK residents, published by Legal and General in 2021, believing multi-generational living would grow in popularity. While for some that way of living may be a financial necessity, the survey found others were attracted by the potential to enjoy closer family links and share household tasks and bills.

Conclusion

Legal & General says its survey results show “there is no formula for family living”; the same could be said today for other groups in society, from young digital nomads to empty nesters and the elderly. That presents challenges in planning, designing, delivering and managing cohesive neighbourhoods and balancing the needs of individual groups, with co-living particularly prompting some local concerns because of the scale of development proposals and their transient residents.

New typologies and tenures may have a significant impact on neighbourhoods but provide affordable ways of living that are already proving attractive with consumers. With their potential to strengthen family units and bring together people with similar lifestyles and work interests, mitigating loneliness and social isolation, they could also ultimately be good for people.